Alex Wang responds to Riley Griffin’s article, “Two Big Drug Flops Show How Health-Care Economics Have Changed” (Bloomberg Businessweek).

Alex Wang is a PhD student at MIT working on engineering physiologically-relevant in vitro liver models. He plans on graduating in the fall of 2020.

PCSK9 Inhibitors: Life-Changing Drugs for Heart Disease

Heart disease is the most fatal and prevalent disorder in the United States, costing over 600,000 lives and over $200 billion every year. A critical risk factor for developing heart disease is having high cholesterol, a common condition estimated to affect over 1 in 10 adults or around 60 million Americans. Over the past few decades, millions of people with high cholesterol have been successfully treated with a class of drugs called statins. Statin medications, which slow down cholesterol synthesis, are now a ubiquitous, safe, and cheap class of generic medicines that have kept many alive and out of hospitals. There remains a significant population, however, for whom statins are not as effective, and there have been few alternatives—until recently. In 2015, Sanofi and Amgen launched the first of a new class of cholesterol-lowering drugs called PCSK9 inhibitors. PCSK9 inhibition is an elegant and highly effective way of lowering LDL-cholesterol by turbocharging the body’s own cholesterol elimination system.

Despite their life-changing potential for millions of patients, PCSK9 inhibitors have failed to reach even a fraction of its target population. In the media, these drugs have been accused of being overpriced, becoming a case study about a drug’s value to society and the increasing power of gatekeepers between patients and drug companies. With PCSK9 inhibitors given list prices of ~$14,000 a year, insurers and drug valuation experts argued that these were too expensive to give to everyone who needed them, and thus the insurers severely restricted access to the medications. Approximately half of patients prescribed these drugs by their doctors were denied, and those who were accepted were then burdened with high copays, leading to even fewer who could get access.

The Pricing Debate Exposes Flaws in the Healthcare System

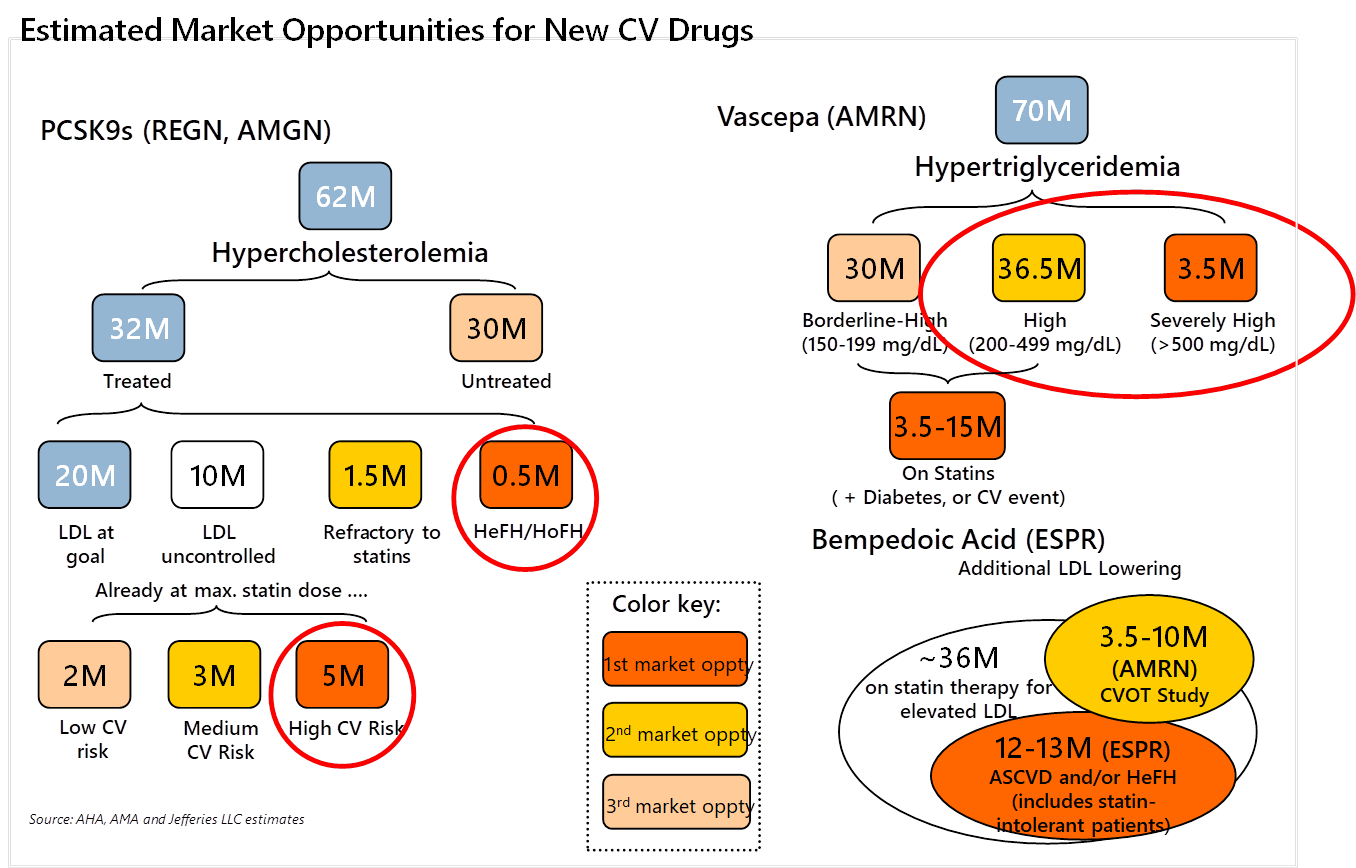

Were insurers right in severely restricting access to these drugs based on price? One commonly cited study that payers and the media pointed to asserted that there would be a staggering $120 billion per year increase in the cost of prescription drugs if all eligible patients were to take PCSK9 inhibitors. Even Lipitor, a statin that and the best-selling drug of all time, made ~$95 billion over its entire patent life. It would be an astonishing burden on the healthcare system if these second-line high cholesterol drugs could cost over $500 billion to society over their patent lifetimes. The study was clearly exaggerated and misleading, as the list price of the drug is never actually paid in full. Furthermore, although millions of patients may be eligible to take PCSK9 inhibitors (Figure 1), the fact that they require injection and are only prescribed after statins prove ineffective makes the actual patient population size smaller.

Source: Jefferies, LLC

This is highlighted by the fact that Esperion’s Nexletol (bempedoic acid), a statin alternative far less effective than PCSK9 drugs, is much lower priced and taken in pill form but has an estimated peak penetration of just 1.8 million patients. As such, rather than considering every single eligible patient, drug companies made the initial PCSK9 list price according to more realistic assumptions of who will be prescribed and actually take the drugs.

In a testament to the mess that is the current U.S. healthcare system, the actual cost of PCSK9 inhibitors is unknown, as the discounted rebate price off the list price is kept confidential. Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), as the Bloomberg article points out, enjoy the spoils of negotiating substantial rebates off drugs’ list prices, keeping those savings rather than passing them on to patients. The fact that PBMs demand rebates obligates drug companies to create room for those rebates by launching with higher list prices, which stokes public outrage. Watchdogs, however, took the list price of PCSK9 inhibitors at face value and tried to make economic arguments over its cost-effectiveness and benefit to humanity. Aside from basing their analysis on list prices, these analyses also failed to consider that these drugs would someday go off-patent and become less expensive, while permanently upgrading our standard of care.

But payers didn’t take the long-term view. Insurers were terrified that a potentially large segment of the population (Figure 1, approximately 5-8 million people) would be eligible for the drugs and simply did not want to pay for them. They couldn’t quantify the benefits of patients avoiding heart attacks because the short-term cost savings are negligible, and when patients do save money by not having to get expensive heart surgery or hospitalization, it may be many years down the line. This calculation, combined with consolidation among insurers and PBMs, is giving rise to a system of misaligned incentives. Proof that insurers and PBMs did not care to cover patients came when drug companies responded to weak demand by slashing list prices for PCSK9 drugs. As the Bloomberg article points out, this barely budged the PBMs, as most of them preferred the higher price and more substantial rebate, which led to insurers deliberately denying patients the cheaper version of the drugs and continuing to charge high copays. From this debacle, Sanofi, co-developer of PCSK9 inhibitor Praluent, has cut back its efforts on developing heart disease drugs. If no one is willing to pay for heart disease drug innovation, then the impetus for drug companies to develop evolved or new classes of heart medications will fade.

We’ll get another chance to see how the world responds to a new drug in this class. Novartis’ PCSK9 inclusiran is an RNAi agent that requires only two shots a year, far more convenient than Amgen and Sanofi’s antibody drugs that require injections twice a month. Despite (or because of) the failure of the first PCSK9 inhibitors, Novartis has partnered with the U.K.’s National Health Service in a population-wide agreement to provide the drug to high-risk heart disease patients. However, the UK is known for being willing to deny patients access to medicines unless it gets big discounts from drug companies, so the real question is whether Novartis will generate enough revenue in America to have made the development of inclisiran worthwhile.

Getting Medicines to Patients Who Need Them

How do we make sure people who need PCSK9 inhibitors get them both now and in the future? The most challenging issue is navigating the system of skewed motivations, as evidenced by the PBMs, and the mistrust among drug companies, payers, and doctors. Legislative reforms are needed to eliminate the misaligned incentives of the PBMs, who have every motivation to keep drug list prices high so that their rebates can be larger. PBMs should be required to pass their savings to the pharmacies and patients rather than keeping the payments for themselves. Doing so would eliminate the motivation for PBMs to keep list prices high and avoid future debacles where lowering the drug list prices do nothing for covering more patients or reducing their costs.

For future generations to be guaranteed access, the most effective step would be to move toward universal health coverage with negligible or zero copays and deductibles. We need to trust that doctors who prescribe medicine to patients know what they are doing, and patients should take comfort that insurance allows them to afford appropriate care, since that is what insurance is meant to do.

Once PCSK9 drugs go off-patent, millions of people will have access to a cheap, effective way to lower their cholesterol. Society will be able to benefit from this medicine for the foreseeable future – a critical aspect of the Biotech Social Contract. We need to ensure PCSK9 drugs, though they are harder to make generic, drop drastically in price when they go off patent through generic competition and regulation if necessary. Innovation, both novel and incremental, require time, money, and effort by hundreds of researchers, investors, doctors, and businesspeople. Indeed, we should continue to acknowledge their contributions even after these drugs go generic. Beyond statins and PCSK9 inhibitors, there are other innovative branded drugs such as bempedoic acid, which lowers cholesterol and Vascepa, which lowers triglycerides, that await eventual genericization. Further in the future, the next innovative class of heart disease drugs may be using antisense therapy to reduce Lp(a), a lipoprotein that is implicated in heart disease but isn’t lowered by any current existing drug. When these drugs become part of the generic armamentarium, patients will have multiple, potent ways of reducing their risk from dying of heart disease. We must ensure that these innovative drugs continue to be developed for all diseases, get these medicines to patients who need them, and celebrate when they go generic. Collectively, these innovations will provide immeasurable benefits for us, our children, and for society.